Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva on Trump, Putin, and a collapsing global order.

By Jon Lee Anderson

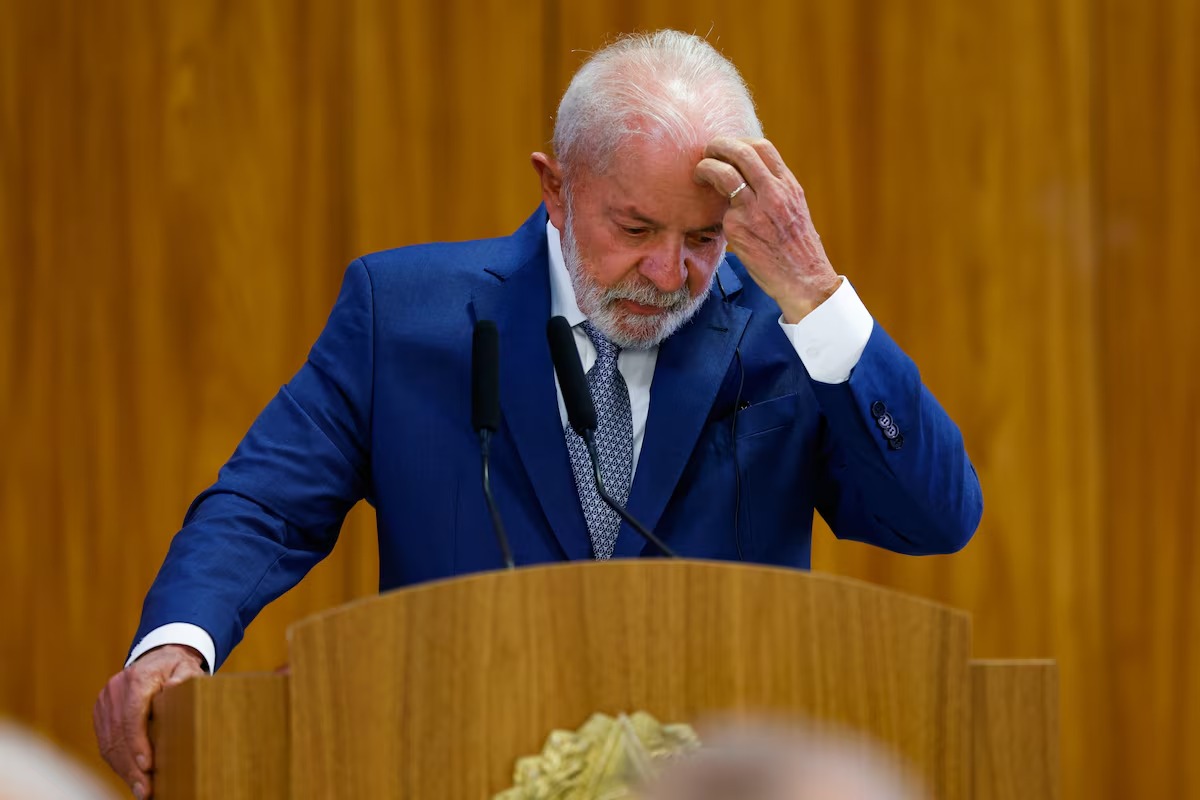

Not long ago, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva met me in his office in Brasília and told me that he'd had a disturbing dream. In recent months, Lula had turned seventy-nine and undergone emergency surgery for a brain hemorrhage, and although he seemed fit and healthy when we met, he was in a reflective mood. He'd dreamed the night before about his predecessor José Sarney, who is now ninety-four years old. Sarney is a cherished figure in Brazil: in the nineteen-eighties, he became the country's first President to take office after two decades of military rule. "In my dream, he came to my house and slept on the floor, and in the morning I made him breakfast," Lula said. "I woke up worried, wondering if something had happened to him during the night."

Sarney turned out to be fine, but it is no accident that Lula was concerned about an emblem of democracy. He told me that the entire Western system felt imperilled. "The democracy we learned to live with after World War Two, the functioning of multilateralism as an important role in relations between states, the respect for diversity, the sovereignty of each country is now fading," he said. "What comes next, we don't know." The entire post-Second World War order, created largely through the intervention of the United States, seemed on the verge of collapse. "We thought we were creating a more civilized, more solidarity-based, more humane society," he said. "The result is worse. It's as if there is a lamp, and when you open the lid the evil people come out."

Lula has built a career on unwavering leftist principles, but he has also long prided himself on his ability to get along with a variety of leaders. Now, though, he confessed that he was flummoxed by the right-wing populists and anti-globalists gaining power around the world. At the United Nations General Assembly last September, he'd tried to organize a meeting of progressive Presidents. "When we sat down to make the list, I discovered there were no more progressives!" he said. In Latin America, only a small group of left-leaning leaders remains, including Gustavo Petro, of Colombia, Gabriel Boric, of Chile, and Claudia Sheinbaum, of Mexico. "In order to keep the meeting from being too small, I changed 'progressives' to 'democrats,' so I could invite Biden, Macron, and other people," Lula explained. "We've had two meetings since then, to discuss how to create a narrative to justify the importance of the democratic system as the best thing ever created for humanity's coexistence-a system with rules, where everyone has rights, and someone's rights end when they infringe on the rights of others. It's what worked in the world. Monarchies, empires-they didn't work. Nazism didn't work. Stalin's communism didn't work."

In his country and in the U.S., he suggested, large portions of the populace seemed to have lost their grip on reality. "There are people who believe things that everyone should understand are lies, because they are so absurd," he told me. "And my concern is how we are going to build a narrative to destroy this." The troubling thing, he said, is that "we still don't have an answer."

Part of the problem was economic, he said. "Democracy starts to fall when it no longer meets the people's interests. Since 1980, the working people in countries that built welfare states have only lost, while income concentration has increased. So what response can we give to Brazilian society? And to German and American society?" There was also a question of leadership. "The U.S. was the mirror of democracy, the pillar of democracy for the planet," he said. "Despite being the country that wages the most wars, it's the country that talks the most about peace, the most about democracy. And yet now there is Trump, who sometimes behaves like-" Lula stopped himself, then continued. "I saw a speech of his in the U.S. Congress recently, and it was absurd-those Republicans clapping at whatever nonsense he said. It was almost the same kind of speech that anarchists used to make in Italy and Brazil at the beginning of the century, calling for a society without institutions, a society where the empire of capital rules."

President Donald Trump made clear his interventionist intentions toward Latin America as soon as he resumed office; in his Inaugural Address, he vowed to "retake" the Panama Canal. Since then, most leaders in the region have handled Washington with elaborate care. The right-wing populists strained to display their loyalty and affinity. Javier Milei-a hard-line libertarian who has slashed away half of Argentina's government ministries-gave Elon Musk an engraved chainsaw and hailed Trump as "one of the two most relevant politicians on planet Earth." (The other, of course, being Milei.) He has been rewarded with U.S. support for a twenty-billion-dollar International Monetary Fund loan, and with praise from Trump, who has said that Milei is doing "a fantastic job."

In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele offered to allow the U.S. to deport its undesirable migrants to his country, to be held in an appalling hellhole of a prison. When Bukele recently visited the Oval Office, he and Trump traded smug jokes about their arrangement, with Trump saying that he'd like to send "homegrowns," too, and Bukele scoffing at the suggestion that he would return the wrongly deported migrant Kilmar Abrego Garcia to the U.S.

Among the region's leftist leaders, Colombia's Petro was the first to resist Trump. After refusing to permit U.S. military planes carrying deportees to land in Colombia, he suggested on social media that Trump was a "white slaveowner," while comparing himself to Colonel Aureliano Buendía, the doomed hero of "One Hundred Years of Solitude." Trump retaliated by announcing punishing tariffs and a sweeping prohibition on U.S. visas for Colombian officials. Within hours, Petro had relented, and his humiliation provided an object lesson for other leaders.

In March, a Hong Kong-based company named CK Hutchison Holdings agreed to sell its ports on the Panama Canal to a consortium led by the American investment company BlackRock. Trump quickly claimed that he was effectively reasserting control over the canal. Panama's President, José Raúl Mulino, tried to salvage his dignity with defiant public statements, but he has mostly succumbed to pressure from D.C. Last month, Panama and the U.S. signed an expanded security-coöperation agreement that allows American armed forces to occupy several former military bases along the Canal Zone. In a joint statement on the new security relationship, released during a visit by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, a sentence acknowledging U.S. respect for Panama's sovereignty was pointedly excluded from the English-language version. Panamanians have grown frustrated. An influential friend there wrote to me, "Mulino has not stopped giving his ass to Trump at every turn, in exchange for nothing."

Mexico's President, Claudia Sheinbaum, has made more convincing displays of composure, but she, too, has avoided confrontations with Trump by giving him what he wants. As my colleague Stephania Taladrid detailed recently, these efforts have included stepping up Mexico's security presence at the border, handing over high-level narco-traffickers to the U.S., and significantly increasing seizures of fentanyl. Even Venezuela's would-be revolutionary leader, President Nicolás Maduro, congratulated Trump for returning to the White House and agreed to hand over American prisoners from his country's jails. After the Trump Administration deported hundreds of alleged Venezuelan gang members to Bukele's prison, Maduro issued a statement denouncing the action as "fascism"-but he was careful to address it to Bukele directly, rather than to Trump.

Lula and Chile's Boric have been the most outspoken Latin American leaders. On a recent state visit to India, Boric described Trump's Inauguration, with Big Tech billionaires "paying fealty to a new wannabe emperor," as reminiscent of "something from another era." He criticized the tariffs as "irrational" and "unsustainable." Although his country's main export commodity, copper, had so far been exempted, Boric promised to seek out new trade deals with India, Japan, and others. He warned that if Trump did place tariffs on Chile's copper-eleven per cent of which went to the U.S. last year-the higher cost would ultimately be passed on to American consumers. "The law of the strongest has short legs," he said.

Lula knows that his coalition is thin. In a recent speech, he said, "The Presidents of South American countries should understand that we are very weak if we are isolated." When I saw him in Brasília, he made a plea for greater international coöperation. "We have to convince the world that it's not possible to end multilateralism," he said. "Multilateralism was a form of civility found among states to coexist peacefully, with rules that everyone must follow," he went on. "It's already proven that, if we don't control the air, everyone will be a victim of air pollution. If the sea rises, everyone will be a victim. It hasn't yet reached the world's most important leaders that we need global governance to make some decisions globally."

Lula noted that the environment was among the most pressing global issues, but he also acknowledged the limits of multilateralism in dealing with it. This year, Brazil will host the COP30 climate conference, in the city of Belém-a location, at the edge of the Amazon, chosen to bring attention to the crisis of deforestation. Yet it is hard to imagine that it will bring radical change. European countries in particular seem likely to donate less as they scramble to devote more of their budgets to military expenditures. Lula shrugged this off. "I do not believe in money from developed countries," he said. "They promised a hundred billion dollars in 2009, and they have not yet delivered. It has been sixteen years. Now the need is 1.3 trillion dollars-and they will not deliver."

Lula advocated a world in which the major powers could compete without resorting to warfare, and in which they coöperated more closely on such priorities as hunger and climate change. It was not lost on him that Brazil, as a developing economy, depends on maintaining friendly relations, even when it means partnering with countries with wildly divergent value systems. "We need to say: thank goodness we have China that, from a technological perspective, is very advanced and can compete in the technological world of A.I., giving us an alternative for this debate," he said. In his telling, Western powers' animosity toward China was spurred by trade, not by its human-rights abuses or its threats to invade Taiwan. "I am from a generation that learned in the nineteen-eighties, through Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, that the best thing for the world was globalization and free trade. Products should flow freely across the world. Money should flow freely across the world." China, he said, had merely adopted this theory along with everyone else. "China started producing everything that was produced in the U.S. and Europe. You couldn't buy a single pair of pants, shoes, or a shirt that didn't say 'Made in China.' They very skillfully copied everything and learned how to produce things as well or better. Now that the Chinese have become competitive, they have become the world's enemies," he added testily. "And we don't accept that. We don't accept the idea of a second Cold War. We accept the idea that the more similar countries are-technologically and militarily advanced-the more they must talk to each other, because I'm not sure the planet can handle a Third World War."

Lula insists on pacifism in an idealistic way that is unusual among world leaders. "Last year, the world spent $2.4 trillion on weapons, while seven hundred and thirty million people go to sleep every night not knowing if they'll have breakfast when they wake up," he said. "That should be humanity's main concern." Even after Russia invaded Ukraine, he resisted taking sides. He described a recent meeting with the German Chancellor: "My friend Olaf Scholz came here, sat on that couch, and asked Brazil to sell missiles to him so he could send them to Ukraine. I told him I wouldn't sell, with all due respect, because I didn't want any Ukrainian or Russian to die with a Brazilian weapon."

Like some others on the left (and many on the right), he criticized the U.S. and Europe for funding efforts to confront Putin in Ukraine. "When you corner the enemy, you need to have the strength to defeat that enemy, and it's not easy to defeat Russia," Lula said. "I discussed this with Biden. And Biden kept saying, 'We're going to destroy Putin, and he'll have to rebuild Ukraine.' What's going to happen now? If peace happens, organized by Trump, he will win the Nobel Peace Prize, and Europe will have to pay for NATO, will have to finance the war, and will have to rebuild Ukraine."

A few weeks earlier, Lula had urged Russia to halt the war. "I called Putin and I said, 'Putin, I think it's time for you to return to politics. Put an end to this. The world needs politics, not war. You're missed. There are not enough people to sit around the table and discuss the fate of the planet: What do we want for humanity?' "

Lula ridiculed Trump's desire to take over Greenland and Canada. "The only thing left for him to take over is Antarctica," he said. "Why do Russia and the U.S. want to increase their territories if they can't even manage what they already have?" In his view, the global posturing by Trump, Vice-President J. D. Vance, and Musk was a serious threat. "They are deniers of the institutions that guarantee democracy worldwide," he said. "The fact that the U.S. Vice-President interferes in Germany's politics is already a crime. I have never gone to another country to interfere in an election!" He suggested that the bellicose rhetoric would eventually harm them. "At first, it may look good," he said. "But the result could be much worse than what they are criticizing. When you release a wild beast, afterward you don't know how to control it."

Not long before we talked, the U.S. government had announced a twenty-five-per-cent tariff on Brazilian steel. "There will be reciprocity," Lula said. "But, before there is reciprocity, we want to show the U.S. what two hundred years of diplomatic and commercial relations between Brazil and the U.S. represents." He pointed out that the U.S. had a seven-billion-dollar trade surplus with Brazil last year, the steel imports included. "What the U.S. imports from Brazil, they transform and then export back to Brazil," he said. "It's a two-way street, so I think this will be harmful to the U.S. For our part, we want to negotiate diplomatically. If there's no possibility, we will take action."

When I asked Lula if Trump had reached out to him, he said no. "If, as a representative of the American state, he wants to talk to Lula, the representative of the Brazilian state, I will talk to him calmly," he said. "But so far I haven't had any interest in talking to him, either. If I ever have a problem and need to call him, I will call him."

The New Yorker

https://www.newyorker.com/news/the-lede/brazils-president-confronts-a-changing-world